9 min to read

What is Mindfulness?

As defined by Prof. Kabat-Zinn, a leading scholar in the field, mindfulness is paying attention in a particular way. It entails developing the ability to focus attention on what is happening in the here and now without any regard for the past or future. It is present-focused attention to what is going on within ourselves and what is going on around us while remaining centered. It is intentionally placing our attention on one thing at a time without becoming attached to it. When we hold a mindful attitude, we bring our full attention to whatever may come up with no judgment and experience the moment more authentically.

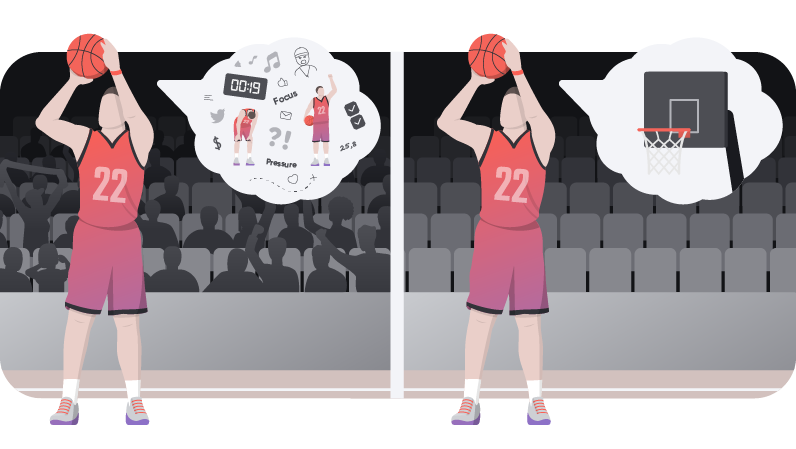

Turning off autopilot

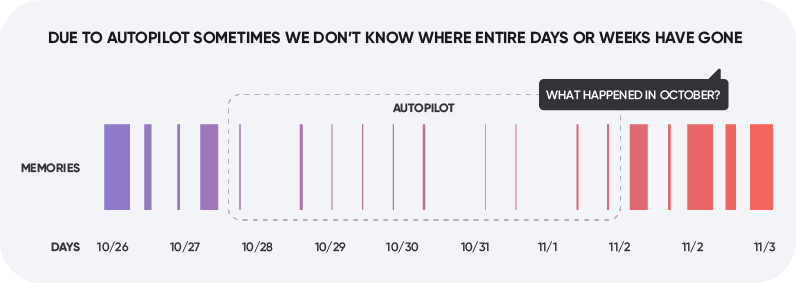

Consider this situation: you had a hectic day at the office, and at the end of the day, you get in the subway to go home. The next thing you know, you are at your house. You made it home safely, but you don’t remember the process of getting there: the stops, the people, the motions. This is an example of being on autopilot, and many of us often live in this state. Sometimes we don’t know where entire days or weeks have gone. Our mind is cough up worrying, planning, judging – but for what? If we don’t have an awareness of our internal state and external environment, it is hard to imagine how our actions will be astute or our decisions wise. Mindfulness helps us turn off the autopilot mode by teaching us to observe and experience reality as it is, be less critical, and live in the moment more effectively.

How does mindfulness relate to meditation?

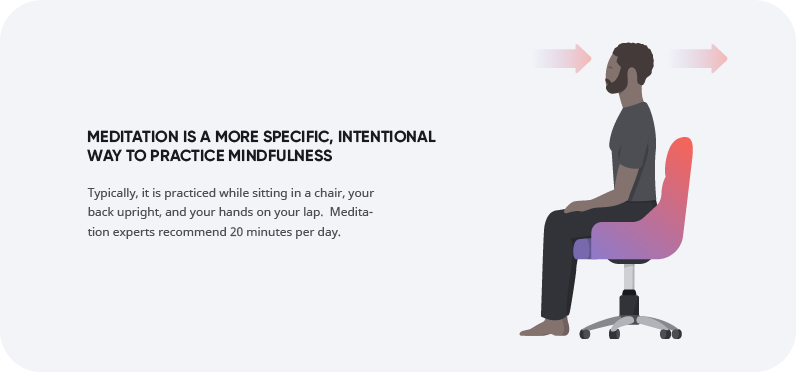

Meditation is an intentional, prescribed way to practice mindfulness. You can practice mindfulness any time by simply being engaged in the present moment and paying attention to whatever you are doing, feeling, and thinking. Meditation, on the other hand, typically requires its own separate space and time. In its most traditional form, meditation is practiced with your eyes closed, sitting down, and for a preset amount of time (e.g., 10 or 30 minutes). It generally involves sensing your body, paying attention to your breath, noticing when your mind wonders, and returning your attention to your body and/or breath.

So, while mindfulness can be practiced in informal, unstructured ways, you always have the option of doing it more deliberately and formally by incorporating meditation into your routine.

How to be mindful

Mindfulness practices occur on a spectrum, from simple to elaborate. In the beginning, it is important to learn to regulate attention – to focus on relevant contextual cues while dismissing aspects of our experience that do not require any response or consideration. By doing this, you will effectively and accurately integrate new information; the many distractions of daily life no longer enslave you.

After you learn to control attention, the goal is to acquire mindfulness skills that involve changing your relationship with your thoughts and feelings. Below we describe how such skills increase in complexity as you progress from noticing to describing, allowing, and finally distancing. We also describe the critical components of a mindful attitude, which involve embracing a nonjudgmental stance and focusing on one thing at a time.

So, here is what you need to do to be mindful:

1. Notice

Noticing is based on traditional meditative practices that anchor your attention on physical experiences, either internal or external. While this practice sounds simple, it can be tough to quiet down a busy mind, especially at first. Typically, focusing on breathing or noticing certain bodily sensations can be useful anchors for this type of practice. It helps you return to the point of focus that is easy to find when your mind wanders. Like exercising a muscle, the more you practice, the stronger you will become in shifting your mind away from extraneous thoughts and cues.

You can practice noticing using all your senses. For example, on a rainy day, you can draw your attention to how the air smells. In the shower, you can mindfully feel the water touching your body. When listening to music, you can attend to all the different tunes in a song. You can also notice internal sensations in your body – e.g., the pace of your heartbeat or the quality of your breath. If, during this time, your mind starts chatting to you about the past or the future, return your attention to the smell of the rain, the touch of the water, the tunes of a song, or whatever you’ve been focusing on.

2. Describe

Describing what we observe helps us connect with the present and allows us to process what’s on our mind and the emotions associated with it. You can describe a flower in the garden or a thought you have when you see a friend. The key is to be mindful of how certain experiences make us feel without clinging to them or allowing them to overtake us. Instead, we simply name the thoughts and experiences as we watch them come and go.

One way to practice this mindfulness skill involves objectively describing objects around us. You can start with something that you do not have strong feelings about, perhaps a pen, a watch, or an acorn. First, explore the object visually. You should describe the object’s inherent qualities rather than your own interpretation or judgment. “Large,” for example, is a judgment, while “about a meter long” is a more objective description. You can then use your other senses to describe (e.g., “odorless,” “pointy”). You may want to imagine that you are describing the object to someone who cannot see it.

When you feel ready to get more personal, you can start describing your thoughts, sensations, and emotions. You may say to yourself, “I am having thoughts about the upcoming board meeting,” or “I sense my sweaty hands and my heart beating fast.” You can also use simple labels for your thoughts and experiences (e.g. “judgment”, “worry”, “planning”, “itchy”, “warm”). This practice helps us understand that our thoughts and emotions about a situation are basically that, “thoughts and emotions.” They do not represent the situation itself.

3. Allow

Allowing means that we let the present moment be as it is. Sometimes, when thoughts or feelings are unpleasant, we feel the urge to avoid them or push them away. However, it is generally the case that the more we try to get rid of a thought or a feeling, the larger and more important it becomes.

Allowing helps us to stay in contact with all elements of our experience regardless of how pleasant or unpleasant they are. It does not mean that we are “ok with” the experience or that we resign ourselves to it. It simply means that we do not deny or resist reality.

So, if you experience a distressing thought or emotion, you may want to whisper to yourself “yes,” or “I accept.” You do so to give yourself a cue that you acknowledge, accept, and allow your current experience as it is. Whether you decide to use such verbal cues or not, the goal is to eliminate the struggle that comes from resisting the experience. This means you can take the energy you were spending on fighting reality and use it to consciously decide how to respond or what to do next.

4. Distance

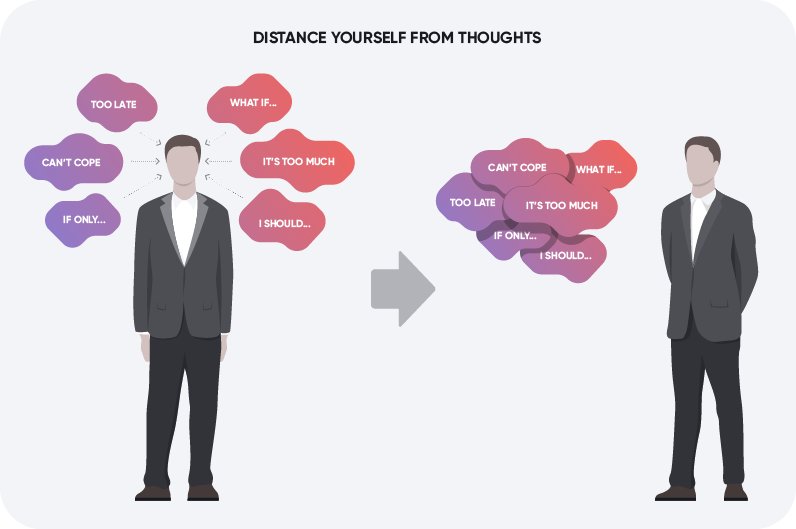

Distancing is the act of creating space between yourself and the things that you think and feel. It allows perspective and self-awareness into the experience of a situation to gain a better, more accurate picture of what is going on. Sometimes, feelings and thoughts can seem so big and powerful that they distort our perception of reality. It is as if a thought or a feeling is presenting itself one inch from the face, and we are unable to see anything past it. Distancing means taking a step back from what is going on inside our minds and, more objectively, evaluating what is going on around and outside of it.

Importantly, when you distance yourself from a thought or feeling, you stop identifying with it. You learn that who you are is not fused with or defined by any limited set of emotions, sensations, or stories you tell yourself. If you can have a bird’s eye view of what’s going through your mind, you gain clarity, wisdom, and serenity to move forward.

Through mindfulness we can step back from our thoughts and observe them, instead of be “in” and consumed by them.

5. Embrace a nonjudgmental stance

To look at our thoughts and feelings objectively, we need to keep judgment and appraisals out of the way. No thought needs to be seen as good or bad, wanted, or unwanted. The goal is to free ourselves from our opinions and let go of the resistance to uncomfortable experiences. This does not mean you will be able to stop judgments from ever arising—that’s impossible. Instead, what you want is to change your relationship to your judgments. Knowing that they’re temporary thoughts and that you don’t need to be carried away by them just because they pop into your mind.

If you catch yourself having a critical or judgmental thought, you can label it as “judgment” without reacting to it. When you actively engage with your judgments, you only see your interpretation of what’s there. Letting go of those judgments allows you to see things as they are. Also, this practice helps you gain awareness of areas where you are overly self-critical or fault-finding.

| THOUGHT | JUDGMENT | RESPONSE / LABEL |

|---|---|---|

| “I can’t believe I said that in the meeting.” | “I always mess up in those situations.” | “Oh interesting, another thought about performance in presentations.” |

| “I ate too much at lunch today.” | “I keep doing that, I’m never going to lose this weight.” | “Interesting, I wonder why I have so many of these thoughts about eating.” |

| “I really need to make sure we get this deal.” | “You might not, you were late in the game.” | “Hmm, I wonder if that thought is driven by a fear of failure.” |

6. Focus on one thing at a time

Our mind loves to multitask, especially in our busy, social media-filled, modern life. But, as much as we can, we should aim to direct our minds towards one task at a time, letting go of all other distractions. You can practice focusing solely on what is in front of you while you eat, exercise, listen to music, and pretty much any other of your daily activities.

At work, we should aim to complete a task without checking our emails or thinking of what is next on our to-do list. When it comes to personal interactions, we should engage fully in our conversations, listen attentively to others without checking our phones, or thinking about what we should say next. This attitude improves our execution of tasks and the quality of our relationships and relieves the stress of being overstimulated.

Arete Training Partner application form

Wow, you’re awesome!

We are happy to see you are interested in Arete. Just give us some time to think and get back to once we are ready. Thank you!

Oops! Something went wrong.

Member support:

support@aretepeakperformance.comWant to become a Training Partner? Please visit Join our team.